When do a doctor's personal beliefs trump medical care?

That's the question being asked after a woman went to an Ottawa-area walk-in clinic for birth control, but was told the doctor refused to dispense such medications. The woman was handed a letter explaining the doctor’s position, which she then posted to Facebook.

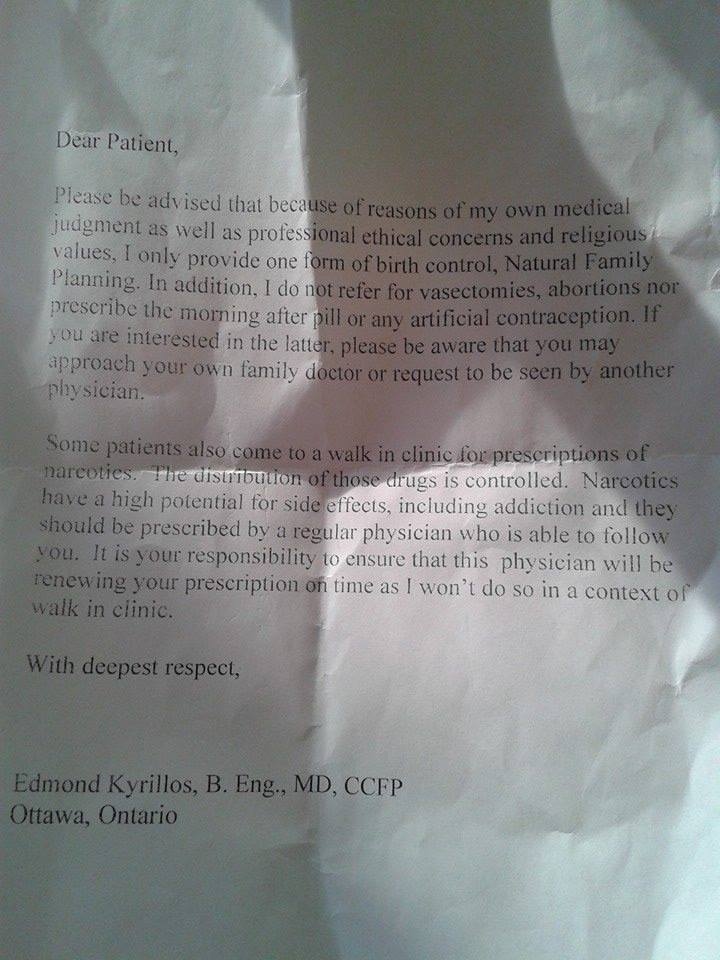

In the note, the doctor, Dr. Edmond Kyrillos, wrote that he did not provide “artificial” contraception due to “ethical concerns.” In full, the note read:

“Please be advised that because of reasons of my own medical judgement as well as professional ethical concerns & religious values, I only provide one form of birth control, Natural Family Planning. In addition, I do not refer for vasectomies, abortions nor provide the morning-after pill or any artificial contraception. If you are interested in the latter, please be aware that you may approach your own family doctor or request to be seen by another physician.”

Arthur Schafer, the director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics, says there are many factors to consider when deciding whether the letter the doctor handed to the woman is ethical.

Schafer says our health care system tries to make reasonable accommodations for the ethical or conscientious objections of health care workers.

But he notes the health system is also concerned with the legitimate needs of patients. And reproductive health and access to birth control, vasectomies, or pregnancy termination are acknowledged as legitimate parts of our health care system to which patients cannot be denied reasonable access.

“So the two are intentioned and there are some circumstances where one should be subordinated to the other,” Schafer told CTV’s Canada AM from Winnipeg.

A doctor would not have a right to deny medical services to a patient based on their own ethics if, for example, she worked in a rural region or a small town, and was the only accessible health care professional. In that case, Schafer said, a doctor would not have a right refuse patients access to legitimate services or treatments.

“And it that violates your conscience, you shouldn’t be practising in that region or town,” Schafer said. “Patients are entitled to services, and they’re entitled to information about the (medical) options that are available to them.”

He added that patients also have a right not to be humiliated or embarrassed by doctors who make them feel there is something illegitimate about their needs.

For that reason, he suggested that a sign on the clinic wall explaining what services are not provided there might be a better way to avoid embarrassment, rather than have patients ask for birth control and be handed a letter in response.

Finally, Schafer noted that walk-in clinics see a variety of patients and requests for birth control are what he calls “a very basic and common need.” He wondered, then, whether a walk-in clinic is the best place for a physician with strong objections to such services.

Schafer suggested if a doctor did choose to work in such a clinic, it would better to ensure there were other doctors available to provide the services that they won’t.

“If you’re not going to provide the full range of legitimate services to your patients at any given time,” he said, “that is a problem.”