In 1935, with the Second World War on the horizon, Nazis forced Jewish-German art dealer Max Stern to sell his collection of 400 paintings.

In the eight decades since then, the works have scattered around the world, making their way into museums and the hands of private collectors.

As his artwork was relocated around the globe, Stern also made his way out of Germany, eventually moving to Canada, where he became one of the most prominent art collectors in the country.

He died in 1987, without reclaiming a single painting—or receiving a penny from the forced sale.

But now, art hunter Willi Korte is on a mission to recover Stern's collection and honour the man who became one of Canada's most important art collectors.

Korte is part of the Max Stern Art Restitution Project, which Concordia University launched in 2002.

As a full-time art sleuth, Korte has travelled around the world, dealing with Interpol and Homeland Security, sifting through archives, and tracing art lost decades ago.

So far, he's recovered 12 pieces of Stern's collection.

"We have been travelling the globe, so to speak, to recover (the paintings) for Max Stern's estate and, basically, Canada," Korte said on CTV's Canada AM on Thursday.

Stern left Germany in 1937, fleeing first to Paris, then London. In 1940, as the war intensified, he left Europe and made his way to Canada, settling near Fredericton, and then in Farnham, Que.

In 1941, he moved to Montreal, where he gained fame as one of Canada's most prominent gallery owners, earning an Order of Canada in 1984, and an honourary doctorate from Concordia in 1985.

But even as he dealt works by Emily Carr and co-ordinated Rodin exhibits, Stern kept his former life and loss a secret.

According to Korte, the dealer never mentioned the art he'd lost in Germany.

It wasn't until after Stern's death that the story of the forced sales emerged, and Korte dedicated himself to recovering the collection.

Though Stern is no longer around to reclaim the art, Korte said it is still important to find the paintings.

He said the work offers important lessons about Nazi occupation, antisemitism, and Stern's personal story.

According to Korte, Stern was an "average" art dealer early in his career, while working in Germany. Though the dealer's collection contained hundreds of paintings at the time, Korte said none of them were of particular value.

"There's nothing in the Max Stern gallery as far as art is concerned that takes us into the category of hundred million dollar paintings," Korte said. "But in a sense that makes it even more interesting."

According to Korte, Stern's paintings represent the type of art that would have hung in the average Jewish home leading up to Nazi rule—and that would have been taken after Hitler came to power.

Of the hundreds of paintings, many feature pastoral landscapes and religious scenes.

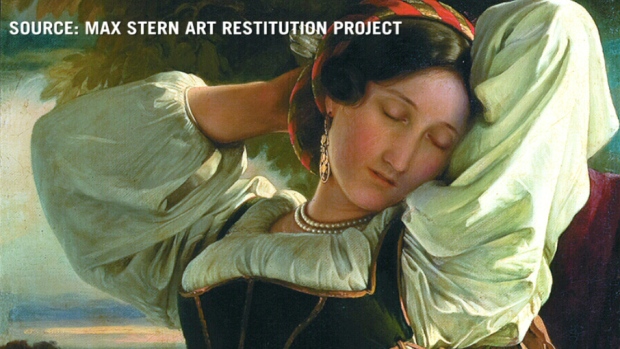

One, titled Girl from the Sabine Mountains, shows a woman reclining, eyes closed and hands behind her head. The painting is believed to be by Franz Zaver Winterhalter, a 19th-century portraitist.

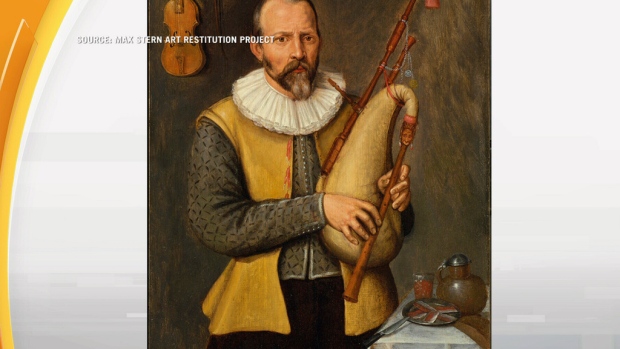

Another recovered piece, Portrait of a Musician Playing a Bagpipe, dates back to 1632. It shows a stern-faced man standing in front of a dark background and holding a set of bagpipes in front of him.

These works, Korte says, help viewers better understand the everyday possessions that Jewish people lost to the Nazis.

However, the unexceptional artwork also makes it more difficult to locate the lost pieces, he said.

"Those are usually very, very difficult to research because they're not as prominent as a hundred million dollar painting."

Still, Korte said he plans to continue hunting for the lost works.

He hopes that privately owned pieces will eventually emerge for sale in the art market, where he can step in to recover them before another buyer picks them up, and they disappear again.