Another member of the Canadian Armed Forces has died of an apparent suicide, the seventh such death in the last two months, while Opposition Leader Thomas Mulcair called on the prime minister to take “urgent action” and address the “crisis.”

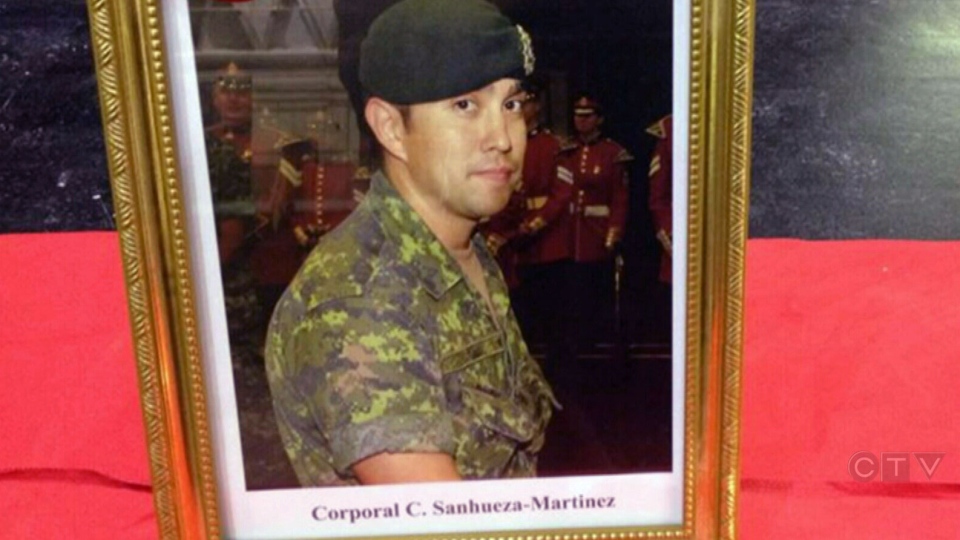

Cpl. Camilo Sanhueza-Martinez, a reservist belonging to The Princess of Wales’ Own Regiment based in Kingston, Ont., died Wednesday. Sources told CTV News it was suicide.

His body was discovered by his partner inside their Kingston apartment on Wednesday.

Sanhueza-Martinez, 28, was an Afghan war veteran. He joined the army in 2005 and served in Afghanistan between May 2010 and January 2011. He had no history of PTSD.

National Defence confirmed the death late Friday evening, but would not go into detail regarding the circumstances.

“The loss of any of our soldiers is tragic and heartbreaking. The regimental family, the entire army family and community are mourning the loss of Cpl. Sanhueza-Martinez,” the statement.

National Defence said that the death is being investigated by the Kingston Police.

Before Sanhueza-Martinez’s death was reported on Friday, Opposition Leader Thomas Mulcair urged Prime Minister Stephen Harper to do more to address the mental health needs of the Canadian Forces.

In a letter addressed to Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Mulcair called the deaths distressing.

The latest suicide came to light this week when the husband of a 20-year Forces veteran came forward to say his wife’s car crash death on Christmas Day was not an accident, but a suicide.

Tom MacEachern said his 51-year-old wife, retired Cpl. Leona MacEachern, had suffered from mental health woes for some time and had recently been diagnosed with PTSD-related major depressive disorder. He said she intentionally drove her car into an oncoming transport truck near Calgary, after leaving a note for her family.

Mulcair says while steps have been taken to improve soldiers’ access to mental health services, “it is clear that these efforts have not been sufficient.”

There have been more than 50 boards of inquiry on military suicides in recent years, Mulcair said, and the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence has heard “countless hours of testimony,” along with ideas on how to better assist struggling soldiers.

“We have also seen successive reports by the Department, the Defence Ombudsman and the Veterans Ombudsman and there remain many recommendations the federal government has not yet implemented,” he said.

Mulcair urged Harper to make the issue “a personal priority.”

"... I am asking you on behalf of your government to honestly acknowledge the crisis, accept responsibility for the fact the status quo isn’t working, and commit to taking urgent action that properly addresses the mental health needs of the men and women who bravely serve this country," he said.

In response to the letter, Prime Minister Harper’s office sent out a statement noting that the government is working with the Canadian Armed Forces and Veteran Affairs in order to address the issue of soldier suicides and mental health issues in the military.

“Our thoughts and prayers continue to be with their families and friends, and the Canadian military family,” Jason MacDonald, spokesperson for Prime Minister Harper, said in a statement.

“What doesn't help is politicizing these losses,” he added. “It's irresponsible for politicians to assert that these services are not available or that jobs will be lost as a result of coming forward.”

Earlier in the day, military ombudsman Pierre Daigle told CTV’s Canada AM that one of the key findings of a report his office issued last year is that there is still a chronic shortage of mental health professionals available to active and retired Forces members.

“And even 16 months after our report, the Canadian Forces are still short of mental health providers,” Daigle said. “In fact, I’d say they’re lacking about 15 per cent of what they really require.”

Daigle said there is currently a shortage of 62 mental health professional positions from the Canadian Forces target of 450 – even while 51 qualified health professionals sit in the candidate pool because of a slow-moving hiring process.

He added though that even if all those workers came into the system tomorrow morning, that would only bring the staffing objective earmarked in 2002 – prior to the Afghanistan war.

“So even that number is not the exact requirement that the Forces will need for the future,” he said.

The other problem, Daigle says, is that many soldiers are not coming forward to ask for help when they need it. He says the stigma problem that has prevented soldiers from admitting they are suffering has improved over the years. But there are still soldiers who aren’t asking for help early enough.

“So if you don’t know who’s sick, it’s hard to give them the proper care,” he said.

The family members of ill and over-stressed soldiers need to come forward too, Daigle said, because it is so often them who are the “first responders” when soldiers begin to break down mentally and help is available.

“They will get support if it’s known that their loved one is suffering from this illness. But if nobody knows, no one will get the proper support,” Daigle said.

“…The impact of PTSD on a family is quite serious,” he added. “So we need people to come forward.”